Jefferson's Draft of the Declaration of Independence (1776)

On June 11, 1776, the Continental Congress appointed a five-man committee

to draft a document declaring independence from England. The committee

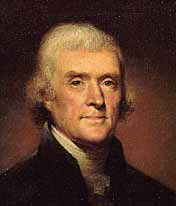

delegated the task to one of its number, Thomas Jefferson, who, in due

course, turned out this masterpiece. The full committee reworked this draft,

and, after nearly 50 alterations (which arguably weakened the document

considerably), the final version of the Declaration of Independence emerged

and, on July 4, 1776, was adopted. In his autobiography, Jefferson wrote

about some of the changes:

"The pusillanimous idea that we had friends in England worth keeping terms with, still haunted the minds of many. For this reason those passages which conveyed censures on the people of England were struck out, lest they should give them offence. The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it. Our northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under those censures; for tho' their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others."

The Declaration of Independence

The final version of the document. Nearly 50 years after the Declaration

had been unleashed upon the world, Jefferson wrote Henry Lee about its

intent:

"...with respect to our rights, and the acts of the British government contravening those rights, there was but one opinion on this side of the water. All American whigs thought alike on these subjects. When forced, therefore, to resort to arms for redress, an appeal to the tribunal of the world was deemed proper for our justification. This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion. All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversation, in letters, printed essays, or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c." (letter to Henry Lee, May 8, 1825)

Authorship of the Declaration of Independence was one of the three accomplishments of his life Jefferson asked to be inscribed on his tombstone. He died on July 4, 1826--fifty years, to the day, of its adoption.

Jefferson's Draft of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1779)

The Virginia statute is one of the great statements of freedom of religion,

and its authorship is one of the three accomplishments in his life that

Jefferson asked to have inscribed on his tombstone. Written by Jefferson

in 1779, this original proposal was slightly reworked by the legislature

under the guidance of James Madison, then passed in 1786. In his autobiography,

Jefferson wrote of it:

"The bill for establishing religious freedom... I had drawn in all the latitude of reason and right. It still met with opposition; but with some mutilations in the preamble, it was finally passed; and a singular proposition proved that it's protection of opinion was meant to be universal. Where the preamble declares that coercion is a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, an amendment was proposed, by inserting the word 'Jesus Christ,' so that it should read 'a departure from the plan of Jesus Christ, the holy author of our religion.' The insertion was rejected by a great majority, in proof that they meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan, the Hindoo, and infidel of every denomination."

An excerpt from Notes on the State of Virginia (1781)

Writing in 1781, Jefferson outlines the ugly history of religious repression

in his home state, which he properly characterizes as "religious slavery,"

and makes one of his most forceful and eloquent appeals for liberty of

conscience. Magnificent work.

Excerpt from a Letter to James Madison (1785)

Writing from France, Jefferson describes extreme inequality of wealth

as a violation of natural right, and an evil against which all wise legislators

will guard. Suggests, among other things, a form of graduated taxation.

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786)

The final version of Jefferson's statute, as adopted by the Virginia

legislature in 1786. The late Jefferson scholar Eyler Coates prepared a

point-by-point comparison of the differences in the two versions here

.

Letter to Edward Carrington (1787)

Another mini-masterpiece. Jefferson, in the aftermath of the Shaysite

rebellion, expounds upon freedom, democracy, dissent.

Except from a Letter to James Madison (1787)

Jefferson's oft-quoted letter about the virtues of "a little rebellion."

He outlines and rates what he saw as the three different kinds of societies

in the world.

Letter to Richard Price (1787)

Jefferson writes to Price

offering hearty praise of Observations on the Importance of the American

Revolution: "I have read it with very great pleasure, as have done

many others to whom I have communicated it. The spirit which it breathes

is as affectionate as the observations themselves are wise and just."

Letter to James Madison (1789)

"...I suppose [it] to be self evident, that the earth belongs in usufruct

to the living; that the dead have neither powers nor rights over it." Jefferson

kicks around some fascinating thoughts on the limits of the power of one

generation to bind the next. The implications are, of course, revolutionary.

Jefferson's exchange with the Danbury Baptists (1801-1802)

An item frequently misrepresented by the religious right, this is the

famous exchange wherein Jefferson described the American experiment in

religious freedom with the phrase "wall of separation between Church and

State." Also included is the original letter from the Danbury Baptist Association

that occasioned Jefferson's response.

Letter to Samuel Miller (1808)

A magnificent little mini-treatise on religious liberty. Forget a presidential

proclamation of a day of prayer and fasting; Jefferson, writing as President,

explains why using his office to even suggest a day of prayer and

fasting would be an inappropriate intrusion of government into religion:

"...civil powers alone have been given to the President of the U S. and

no authority to direct the religious exercises of his constituents."

Letter to N. G. Dufeif (1814)

The subject: Censorship and religious establishments. Jefferson comes

out with both guns blazing.

Letter to Samuel Kercheval (1816)

A classic on various aspects of liberal democracy. Writing about the

constitution of Virginia, Jefferson makes a very important point; that

the government of the state wildly deviates from republican principles

in form, but is forced to adhere to such principles anyway because those

are the principles of the public. "...our republicanism" is to be found

"in the spirit of our people." He suggests reforms that would bring the

government more in line with that spirit, and revisits his theme of the

dead holding no power over living generations, condemning those who "look

at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the arc

of the covenant, too sacred to be touched."